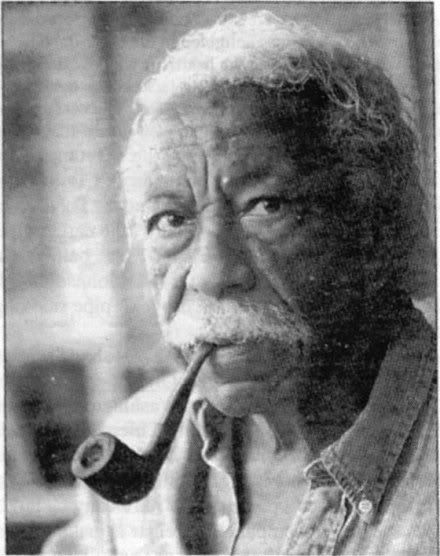

Gordon Roger Alexander Buchannan Parks (1912-2006)

"I had a mother who would not allow me to complain about not accomplishing something because I was black. Her attitude was, 'If a white boy can do it, then you can do it, too—and do it better, or don’t come home.'"

Gordon Parks was born the youngest of 15 children in the segregated town of Fort Scott, Kansas. When his mother died, he went to live with a sister but he did not get along well with his sister's husband, so he left, working odd jobs to get by--only the kinds of odd jobs that were allowed to someone of his skin color in the 1920s and '30s.

In 1938, he bought his first camera after seeing some pictures of migrant workers in a magazine. He was urged on his early path to professional photography by the film developers who developed his first roll of film, as well as by Marva Louis, the wife of boxer Joe Louis. He began a business as a portrait photographer for society's upper crust in Chicago.

A full treatment of Parks' career in freelance photography is beyond the scope of this post, but he worked for

Vogue and became famous for his photo-essays in

Life.

During the 1960s he began writing, turning out the autobiographical novel

The Learning Tree, and several volumes of poetry and memoirs. In 1969 he became Hollywood's first major black director when he directed a movie version of his

The Learning Tree.

In 1971 Parks directed

Shaft, and in 1972 the sequel,

Shaft's Big Score.

He directed

Shaft! you say. What else can be said after that? Well, there's more.

He was a self-taught pianist. He could perform classical as well as jazz, and wrote a

Concerto for Piano and Orchestra and a symphony called

Tree Symphony. In 1981 he published the fiction novel

Shannon about Irish immigrants. He was also a visual artist who created abstract oil paintings based on his photos, and he was a co-founder of

Essence magazine.

Gordon Parks himself said that freedom was the theme of all his works.

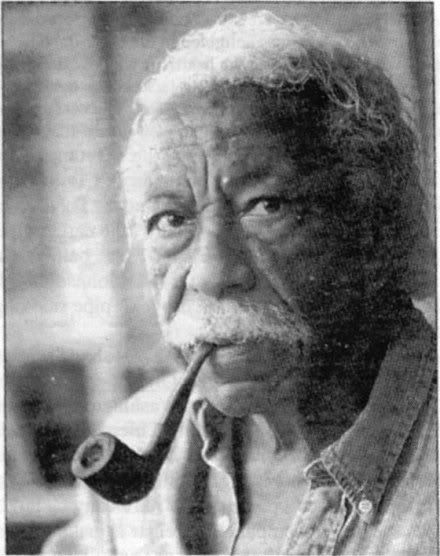

This photo was taken of Carl Jung, with pipe and book, in his library at Küsnacht, at the age of 85, a year before his death. Said Jung of himself: "I am satisfied with the course my life has taken...It was as it had to be."

This photo was taken of Carl Jung, with pipe and book, in his library at Küsnacht, at the age of 85, a year before his death. Said Jung of himself: "I am satisfied with the course my life has taken...It was as it had to be."